Serious Play

Thinking-through-making in the studio

Recently, we’ve been thinking about something the philosopher and urban planning professor, Donald Schön, wrote in 1984: ‘Designing is a conversation with the materials of a situation.’1

There’s something about this that feels particularly resonant: the notion that designing is a dialogue rather than a one-sided spiel, a two-way engagement with the world rather than a retreat from it.

At Superflux, we’re fervent believers in embodied intelligence, and in the idiosyncratic process of experimentation. For over 16 years, our material practice has been informed by the Indian philosophy of jugaad: the art of resourceful adaptation and creativity, of crafting tools from the remnants of our era.

In 2020, Anab coined the term “Craftocene” to give sound and shape to our vision of technology as a regenerative craft rooted in this resourcefulness, and to the way we materialise alternate futures and adjacent presents through the physical act of making.

While the Anthropocene hints at the extractivism of our current age, the Craftocene calls for ingenuity, skill, and innovation to build new tools from the ruins of our collective present. It’s a call to repurpose the waste of late capitalism, and to embrace all life’s rugged nature to survive, not in spite of, but with hope and purpose.

– Anab Jain

At the crux of this practice—one focused on embodied craftsmanship, as opposed to our other more speculative and narrative-led work—is the push to find new ways to adapt, transform, and move forward.

The material artefacts, devices and diegetic prototypes we’ve crafted over the years envision a shift towards more regenerative, circular and restorative ways of being. They propose alternate, craft manifestations of technology, and celebrate the connections between technology and our natural worlds.

Artefacts in the Craftocene

Our first physical foray in the Craftocene was an Arduino spear, which we designed and produced for the Singapore iteration of Mitigation of Shock, our immersive apartment radically adapted for a future in the wake of climate change. Alluding to the ongoing collapse of traditional food systems in the project’s speculative premise, the spear was handmade from an old circuit board, a length of wood, and twine made from a melted plastic bottle. It rested in the future apartment’s hallway as a visceral—and narrative—tool of survival and adaptation.

For our 2021 film, The Intersection, we produced a series of objects that served as diegetic props in the journey from a violent present to a cooperative future. Our server frame pack and array of sensors were situated in the film to draw attention to its complex social, cultural, political and environmental relationships.

Each artefact was hand-crafted by materials that would be available in a future in which mass production has been limited: salvaged hard-drives, discarded electronics and household items, foraged wood, and hand-etched circuit boards. They were physical metaphors, serving both as souvenirs of our present day and as prototypes for a post-crash scenario where technology and the natural world are deeply entwined.

The Vape Battery

While it can be challenging as a small practice to devote time to research and experimentation, we recognise their deep imaginative value. Untrammelled experiments are a core part of the studio’s R&D work: intentional seeds that often spring forth between client projects and commissions, recharging our creative batteries.

Without the time crunch of a deadline, these quests often lead us down unexpected avenues. Some disappear into the ether entirely, while others transform into large-scale projects, or hibernate for when the right moment or opportunity arises.

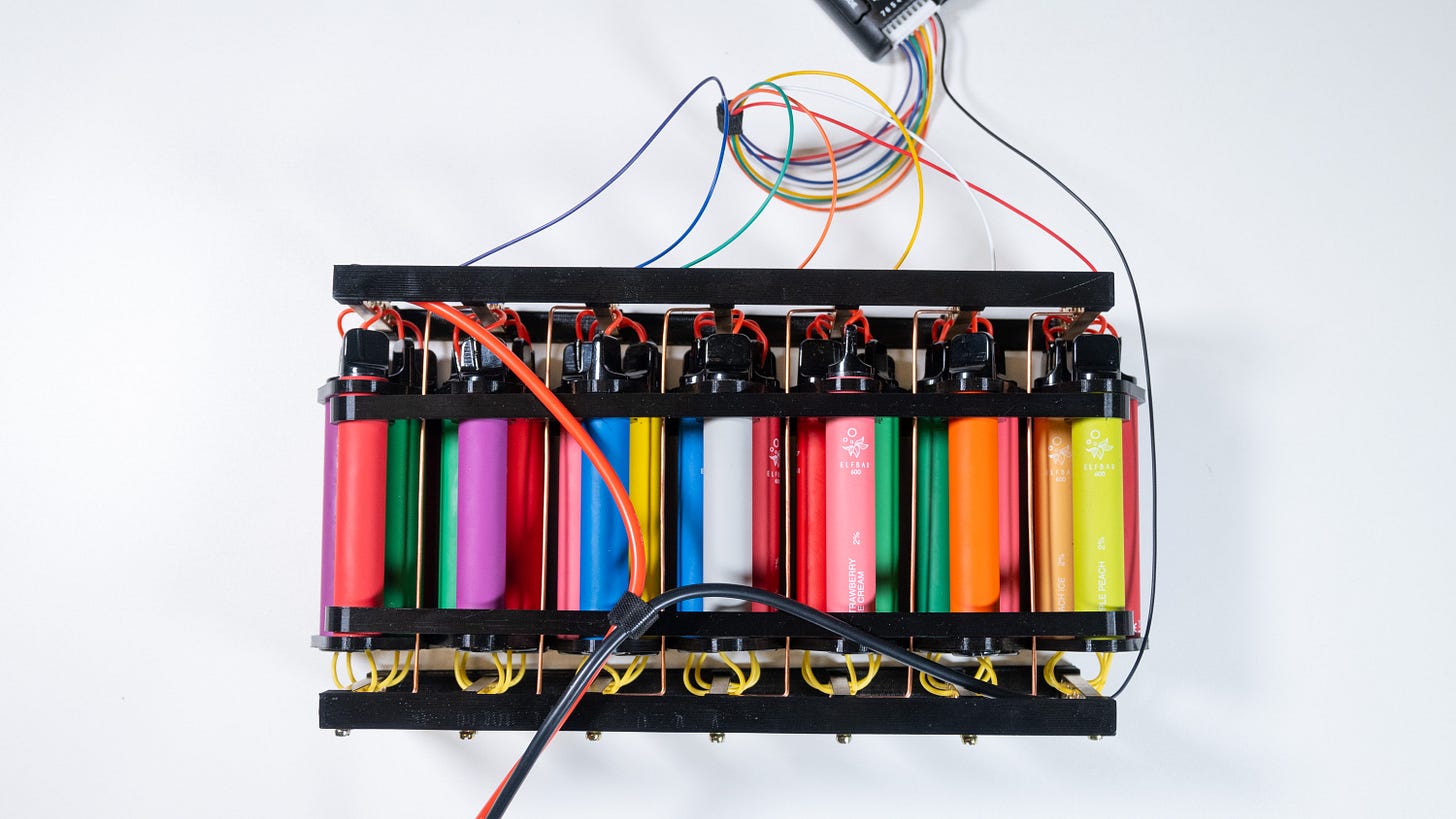

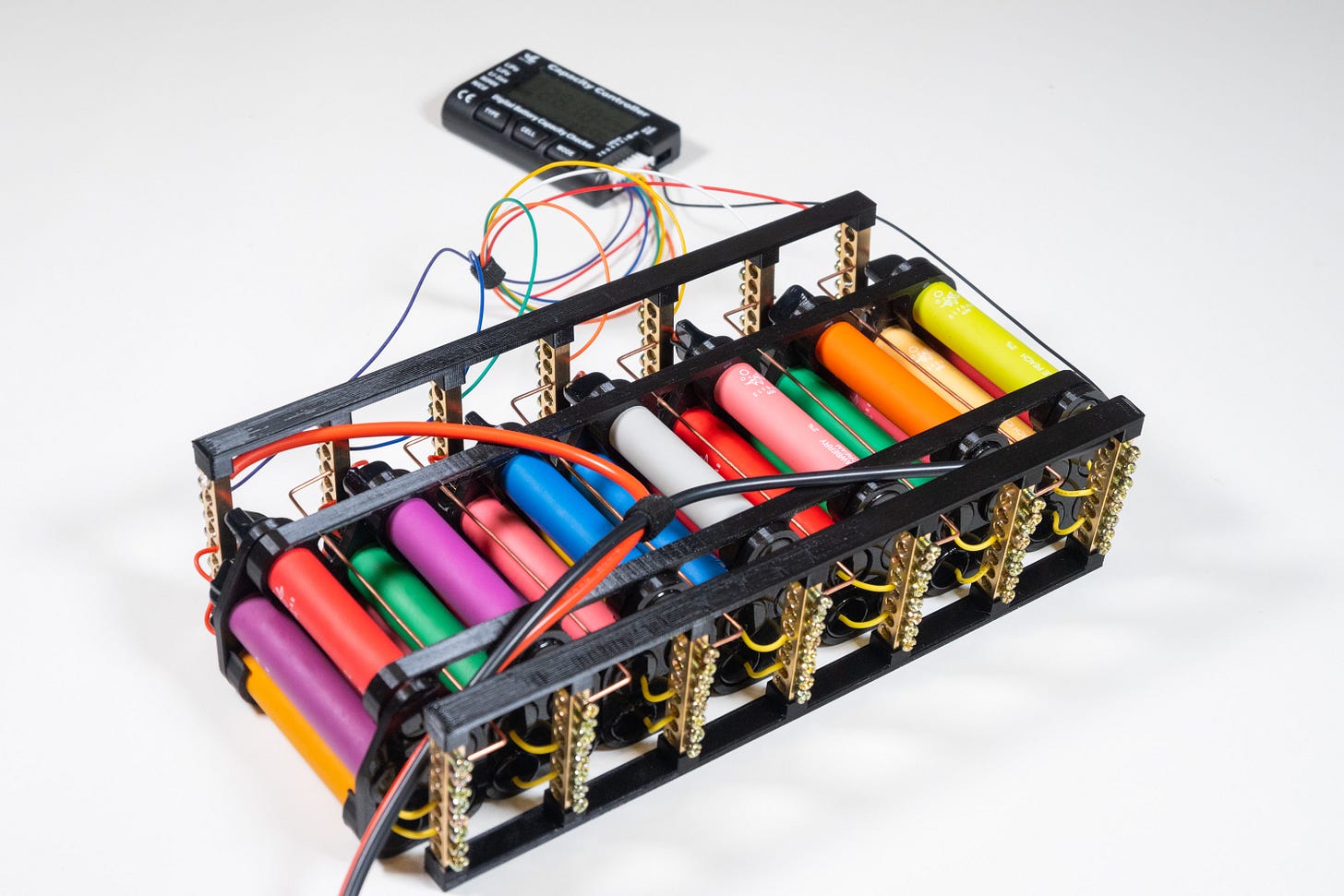

A recent example of one of our Craftocene quests was a battery pack we made from discarded vape batteries.

After observing the growing number of disposable vapes strewn across the pavements of London, we began thinking about what we could meaningfully—or at least just inventively—do to evict these pastel eyesores.

We scoured the streets for as many discarded vapes as we could find, which, needless to say, didn’t take very long. Armed with bagfuls of Elf Bars back at the studio, we shucked them open to excavate their lithium polymer batteries. At the time, we were intending to conclude a project with a website repository of research. Our hunch about repurposing these still potent vape batteries led us to wonder if we could use them to power the solar-run website at night or on overcast days.

After months of experimentation, we successfully created a large-capacity battery from these salvaged batteries, plastic vape casings, and solid copper and brass terminal blocks. The Craftocene battery pack was able to directly charge our website, although we did discover a few hiccups that might require more time to fix.

More than achieving a result, we were fuelled by the process of intentional experimentation. Every iteration was a way of coming at the same idea from a new angle, the goal pleasurably undefined; expansive enough for us to rummage through our ideas in real time and see what fit.

Thinking-Through-Making

“Thinking-through-making” is a term that’s often bandied about but rarely defined, maybe because of its perceived simplicity. It’s actually more complex than we might initially think.

Instead of separating thought from action, this approach to knowledge creation focuses on how understanding emerges through practice. It asks us to step outside of the mind and into our bodies, to engage with the materials of the situation in all their unpredictable tactility. Seen this way, craft becomes a site of encounter and exchange, rather than mechanical instruction.

Ideas come to Anab while she’s on the move: during her travels, while on walks, when she’s outside. For Jon it’s often when he’s cycling, for Léa when she’s swimming or people-watching, and for Ed when he’s using his hands. Carmen rejuvenates creatively through sketching, printmaking and cycling, while Andy is most inspired when he’s gardening or listening to music and sounds in the natural world. Julia’s best revelations emerge when she’s walking outside with no headphones on; for Matt, it’s when he’s looking at things through a camera lens and drawing visual connections. Mon’s ideas arrive when he’s out in nature or strange artificial landscapes, foraging for materials.

These creative moments all have something in common: ideas come when our bodies are activated and sensorially engaged.

Dwelling in the Interstices

In a way, thinking in conjunction with making is an alchemisation of mere concept, a process that adds texture to ideas, enriching them in the process.

In her essay on the ecology of attention, Lia Purpura writes about the beauty of interstitial space in a time before the never-ending scroll. ‘The gap between one activity and another was an open field, a transitional territory. An ecotone. Riparian. Estuarial,’ she observes. ‘What did I do in that interstitial space while walking, or waiting, or in a pause while writing? What actually happened when I sat at that red light, or looked up from the page, kind of lost?’2

These stolen moments of attention can be similarly applied to the lost art of experimentation in the age of automation. In an era where clearly defined deliverables and heavily justified outputs are king, it’s hard to let ideas properly gestate, to give them time to coalesce and totter before they take flight, or shape. We’re unwittingly being asked to become the oracles of our inventions, to be able to predict exactly where our ideas are going to take us.

Everything we know about the world is a process of experimenting, adapting, adjusting. It’s a way of touching the world in different ways and seeing how it responds. It can look very haphazard and jovial, but it's a form of serious play.

‘It's about finding that sweet spot between goal-oriented behaviour and open-ended experimentation,’ Jon has remarked. ‘You're not wandering aimlessly, but at the same time, you don't know for certain what your next steps will be before setting off. You're aware that there’s something potentially interesting in that direction, and so you wander through conceptual worlds, looking to see what treasures might be found.’

What is lost when a process becomes automated? When we curb the act of figuring, that is to say, ‘creating linkages, adjacencies, and intersections’3? When we stop grappling with an idea, teasing out its knots, allowing its unravelling to lead us somewhere unexpected? It’s not that we don’t get the need for a long-term vision in some form. But more and more, rather than being an adventure of equal importance, the process is becoming an inconvenient inevitability squashed between an idea and its realisation.

In an increasingly automated world, we’re in danger of losing this intertwined relationship between thinking and making: two different but symbiotic processes, each with rich inherent value. Replacing emergent, tactile, imagination-led processes—these forms of serious play—with AI prompts strips away something magical. It removes a reciprocal implication with the material world, our sense of acting and being acted upon in return.

Towards an Itinerative Practice

The sonorous duality of thinking-through-making is that it’s an act of improvisation, of adaption, of rhythmic itinerance. We’ve always waxed lyrical about the importance of iterative thinking in our practice, of problem-solving by learning from feedback, incremental progress, and adaptation. But maybe the way forward is to practise, as the anthropologist Tim Ingold suggests4, itineration instead of iteration: to focus on journeying instead of merely repeating.

Experimenting, itinerating, thinking-through-making: these are different garments that clothe what lies at the heart of all craft—exploring the mechanics and mysteries of our everyday world. It requires a certain surrender to the process; an openness to being diverted; a detachment from preciousness.

Real-world problem-solving, on the ground with your bootlaces trailing in the mud, is complex and unpredictable. It’s not clean, not glossy or by the book, but messy. Fertile. The best ideas don’t tend to break fresh ground on undisturbed soil, but in the muck of the unexpected, the way flowers sometimes bloom from a crack in the sidewalk.

This is true for all creative work. As we draw, sketch, make, iterate, and imagine, we bring ideas into being through our craft of choice.

What happens when we’ve achieved all our outcomes, when we’ve passed a finishing line without being able to recall any of the “distractions” along the way that might have pulled us onto entirely different—and sometimes more interesting—paths?

‘Life is open-ended,’ as Ingold writes, in a reminder of the generative joys of experimentation, ‘its impulse is not to reach a terminus but to keep on going.’5

Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

Lia Purpura, ‘The Ecology of Attention’, AGNI (2022) https://agnionline.bu.edu/blog/the-ecology-of-attention/.

Janet Sternburg, ‘The Mind Has a Mind of Its Own: On Maria Popova’s Figuring’, LA Review of Books (2019) https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-mind-has-a-mind-of-its-own-on-maria-popovas-figuring/.

Tim Ingold, ‘The Textility of Making’, Cambridge Journal of Economics 34.1 (2009), pp. 91-102 https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042.

Ibid.